Now that we have covered some fundamental options terminology, we will proceed to delve into the mechanics of options trading.

Options represent legally binding contracts that grant you the right to buy or sell a financial asset. Throughout this course, my focus will primarily be on stock options, although it's worth noting that there are standardized options available for indexes, bonds, and other assets.

There exist two main types of options: puts and calls. A put option provides the holder with the right, but not the obligation, to sell 100 shares of a stock, while a call option grants the right, but not the obligation, to buy 100 shares of a stock.

In essence, an option comprises three key components that demand your attention: the strike price, the premium, and the expiration date.

Strike Price: This represents the price at which the option contract allows you to buy or sell the stock.

Premium: The price of the option itself. The buyer pays the premium, while the seller receives it.

Expiration: The date on which the option ceases to be valid. Each option has a predefined lifespan and expires on a specific date, in contrast to owning shares, which can be held indefinitely.

Here are a few examples illustrating these components:

A January 50 call priced at $0.50.

A March 30 put priced at $1.00.

In the case of the January 50 call, you would acquire the right to purchase 100 shares of the underlying stock at $50.00 per share until the January expiration date. Conversely, the March 30 put would grant you the right to sell 100 shares of the underlying stock at $30 per share until the March expiration date.

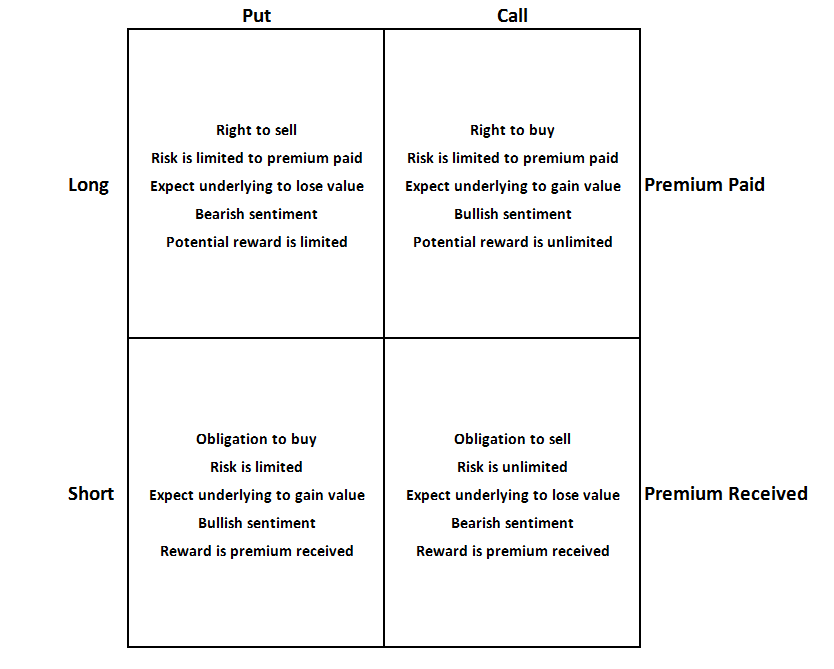

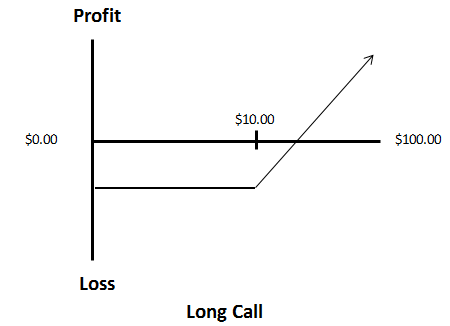

Options trading often revolves around the concept of buying or writing calls and puts. The buyer has the right to execute the transaction, while the seller is obliged to fulfill it. A call buyer anticipates stock price appreciation, whereas a put buyer foresees a decrease. Conversely, call and put writers hold opposing perspectives.

One of the advantages of options trading lies in the explicit risk delineation before entering a trade. As a long option holder, your maximum potential loss is predetermined by the premium paid—an easy-to-understand concept. On the flip side, being short an option involves unlimited risk, as exemplified by a call writer lacking stock ownership.

Stay tuned for upcoming lessons on risk management strategies. Remember that understanding the inherent risks and employing thorough research are indispensable in options trading. For now, grasp that being long an option exposes you to a capped loss risk, contrasting with the open-ended risk of being short an option. In the next lesson, we will explore the dynamics of selling a call without holding the underlying stock, a strategy known as writing a naked call.

Now, let’s turn our attention to the converse side of this transaction.

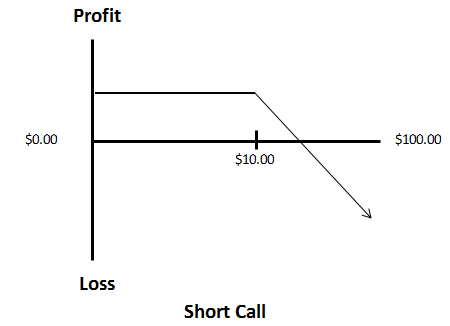

Short Call Option

Suppose you anticipate a decline in the stock's value. In this scenario, you opt to sell a $10.00 call option. While the option premium remains at $1.00, you now receive $100.00, representing the premium amount. If, by the expiration date, the stock's value is at or below $10.00, your option will expire without value. However, you retain the $100.00 collected in premium—the maximum profit you can achieve.

Conversely, if the stock valuation rises, you encounter a potential challenge. Given that stock prices can ascend indefinitely, your obligation to sell the stock at $10.00 may lead to a problematic situation. Essentially, you would be compelled to sell the stock for $10.00, even though you would need to cover the short position at a considerably higher price. This scenario contrasts starkly with the traditional investment principle of buying low and selling high. Here is an overview illustrating the risk/reward dynamics of this particular trade.

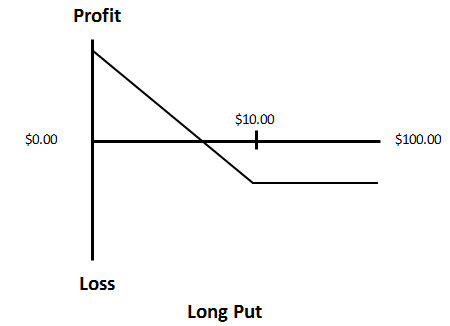

Purchasing a Put Option

Acquiring a put option mirrors the inverse of purchasing a call option. In this scenario, you are anticipating a decrease in the stock price. Should the stock indeed decline, the value of your put option appreciates. Conversely, if the stock ascends, the value of your put option diminishes. Visualizing this relationship can be represented graphically.

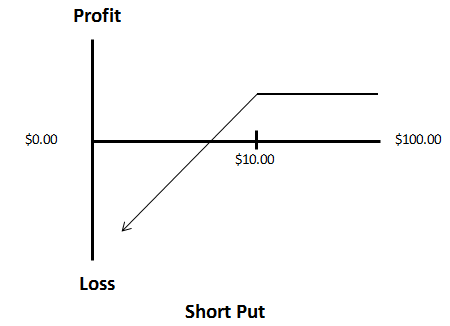

Short Put Option

It's essential to understand that the put seller, in this case, holds a bullish outlook, believing that the stock will in value. If the stock does indeed rise, the trade proves successful. However, it's crucial to note that, for an option seller, the premium received represents the maximum profit potential from the trade. This limitation arises from the fact that in the event of a stock price increase, the obligation to purchase it at $10.00 becomes obsolete—given that sellers in the market would opt to sell at a higher price.

On the other side of this scenario, there is a risk that the stock might decline. If this transpires, the seller remains obligated to purchase the stock at $10.00. Fortunately, in such a downturn, there will likely be numerous sellers willing to transact at a value below $10.00. Consequently, the risk exceeds the $100.00 premium received. However, the risk is capped by the fact that a stock's value cannot plummet below zero. This risk limitation sets selling a put option apart from the potential unlimited risk associated with selling a naked call. Visualizing the risk/reward dynamics for this trade can provide further insight into its implications.

Alright, to summarize everything we've covered, I've compiled a grid to aid in visualizing the fundamental distinctions between puts and calls, as well as the concepts of being long and short in options trading.